Why the Budget strengthened the case for owning short-dated bonds

The Budget will significantly increase the UK’s need to borrow from the bond market over the next five years. Will fears over rising supplies and the price-sensitivity of international investors mean that longer-dated UK government bonds come under pressure? If so, shorter-dated bonds are less exposed to those dynamics while offering equally attractive yields.

With the dust largely having settled after the Budget, investors are left wondering what Labour’s approach to managing the economy – spend, tax and hope-for-the best – might mean for the UK bond market in the years ahead. Our key takeaway was this: Chancellor Reeves’ first Budget increased the risk that the Debt Management Office will flood the market with gilts at a time when their potential buyers are becoming more price-sensitive than ever.

That may sound like a gloomy outlook but our view is that the Budget actually enhanced the relative attractiveness of the short end of the bond market. All else being equal, the increase in gilt supply should be felt most keenly by longer-dated bonds and lead to a steepening in the UK yield curve. So, the Budget reaffirmed our enthusiasm for shorter-dated bonds. We liked that part of the market even before the chancellor stepped up to the despatch box; that conviction is now even stronger.

The Budget will increase the supply of gilts

From the perspective of the gilt market, the first piece of bad news in the Budget was that the spending measures and tax policies it contained would appear to be somewhat inflationary in the short term. As the market’s reaction suggested, that is unhelpful for assets whose payouts are fixed in nominal terms.

Just as importantly, however, it also increased fears of a glut in gilt issuance. The measures announced by the chancellor will mean that UK government spending will rise by around 2% while taxes rise by around 1%. That will result in another £140 billion of borrowing over the next five years1.

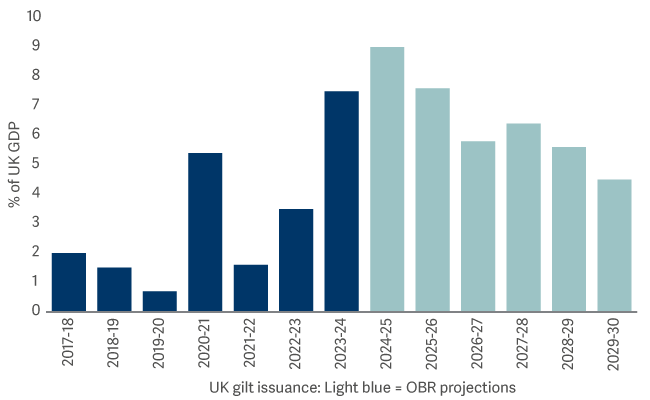

The projected increase in the net supply of gilts is dramatic

The Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR’s) forecast is that central government net cash requirement (CGNCR, which is what ultimately drives gilt issuance) has increased by around £30 billion per year to the end of its forecast horizon2. This threat of increased supply is nothing new, of course. And the UK is not the only country with a deficit problem; the prospect of ballooning government bond supplies globally has been a talking point for months. But that does not alter the fact that the UK government appears to be placing a lot of faith in the private sector’s appetite for gilts remaining robust.

In its post-Budget Economic and fiscal outlook, the OBR acknowledged the size of the challenge ahead:

“The historically high cash requirement, alongside the unwinding of APF gilt holdings by the Bank of England, means the private sector needs to absorb historically high volumes of debt for a sustained period. The forecast for the change in private sector holdings peaks this year at 9.0 per cent of GDP and averages 6.5 per cent of GDP over the forecast period, compared to 2.7 per cent of GDP between 2000-01 and 2022-23.”3

Demand for gilts is still there but it is more price-sensitive and less focused on duration than in the past

So, a lot of gilt supply is on the way. But what about demand?

The demand side also appears to be undergoing structural change. Demand from the former ‘natural buyers’ of gilts, the UK’s defined benefit pension funds, has peaked and is in structural decline. Having once acted as a captive source of demand for gilts through the accumulation phase, the focus of pension funds is increasingly turning towards cashflow matching as they migrate deeper into the buyout and decumulation phases.

To some degree, this structural decline in demand for gilts from pension funds is being replaced by demand from overseas investors. Yet while foreign demand has increased, these buyers are more price-sensitive and less patient. Moreover, these foreign buyers are typically searching for yield as part of shorter-term carry trades and are less focused on duration.

Monetary policy may, of course, ride to the rescue of the long end of the gilt market. But the fiscal loosening delivered by the Budget and the relative resilience of UK consumers means markets may be hoping for lower rates than the Bank of England is able to deliver. Inflation is still too far above target to warrant aggressive rate cuts.

That said, we are in a global easing cycle even if it does turn out to be more drawn out than many hoped this time last year. Lower rates globally should underpin demand for gilts. And, crucially, shorter maturity bonds are more closely anchored to policy rates than longer-dated bond yields, where the longer-term forces of issuance (supply) and structural demand play a larger role.

The case for short-duration bonds is increasingly clear

In the absence of a ‘flight to quality’ triggered by a significant political or economic shock, our base-case scenario is that longer-dated bonds will periodically be buffeted by fears over rising supplies, structural changes in demand from pension funds and by the price-sensitivity of international investors.

No extra yield for owning longer-maturity bonds

That, in turn, should mean that investors will increasingly demand a higher risk premium for owning longer-dated bonds. That premium doesn’t exist today: the yield afforded to investors in 2-year gilts is still broadly equivalent to the yield available to investors purchasing 10-year gilts4. That pattern is mirrored in the investment-grade corporate bond market, where the additional yield for owning longer-dated bonds is virtually zero, versus a pre-pandemic norm of over 1%5.

By delivering a significant measure of fiscal loosening, Chancellor Reeves has not done sentiment towards the UK bond market any favours. But she has, in our view, further enhanced the case for owning short-duration bonds. Are there risks in that part of the market? Certainly. But the volatility here is far lower and the downside should be significantly smaller if rates don’t follow the path the market currently expects. Equally, for investors seeking income, the yields on short-dated bonds are attractive. You might be excused for feeling gloomy about gilts post-Budget but, if you know where to look, there are patches of light to be found in the dark.

2Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2024 - Office for Budget Responsibility 1.1

3Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2024 - Office for Budget Responsibility 6.17

4Source: Artemis/LSEG. As at 21 November 2024, 10-year gilts yielded 4.47% versus 4.402% for 2-year Gilts

5Source: Artemis/Bloomberg as at 30 September 2024. Indices are Markit iBoxx Sterling Collateralized & Corporates (UK Midday) and Markit iBoxx 1-5 year £ Collateralized & Corporates Index