30 years of bond investing: Seeking the silver lining

One lesson Stephen Snowden has learned over the course of his 30-year career is that markets struggle to accurately forecast interest rates. Are investors about to get it wrong again? Might rates need to fall further than anyone currently expects?

I began my career in fund management 30 years ago, in September 1994. The first market-defining event came just a few months later. In February 1995, Nick Leeson’s outsized bets on the Nikkei triggered the sudden collapse of Barings Bank, a pillar of the financial establishment whose collapse seemed unthinkable – until it wasn’t. It was a useful lesson in the tendency of events to confound expectations.

The next three decades brought the Asian financial crisis (1997), the collapse of LTCM (1998), the implosion of tech bubble (2000), a global financial crisis (2008-09), the eurozone crisis (2010-12) and then Covid. So, what have I learned in that time? I’ve learned that episodes of volatility usually present opportunities. But I’ve also learned that the market is pretty bad at forecasting interest rates…

“When the facts change, I change my mind”

When rates fell to practically zero in the aftermath of the financial crisis, l assumed they would pop back to ‘normal’ levels quickly. They didn’t. Expectations – including my own – slowly changed, morphing into an acceptance that rates would need to remain ‘lower for longer’. Then, through a combination of Covid, supply-chain disruptions and the invasion of Ukraine, inflation hit double-digits. This was not something I thought I would ever see in my professional career.

Now that interest rates have peaked, we are all busily guessing what the new R* – the long-term ‘natural’ rate of interest – will be. Having peaked at over 5%, the market is currently pricing UK base rates to be about 3.5% three years from now.1 I would argue that they have much further to fall than that.

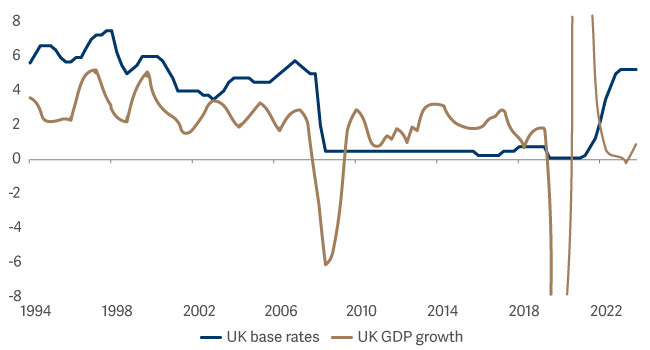

Given my record in making predictions, feel free to take my expectation that base rates will need to fall significantly from here with a large pinch of salt; I’m fully prepared to change my mind if the facts change. But the facts today tell me that interest rates are out of step with the UK’s anaemic economic growth.

Why I expect rates to fall meaningfully from here

The last time base rates in the UK were above 5%, the world was a happier place. Daniel Craig had just starred in his first Bond movie, Casino Royale, and Steve Jobs had just unveiled the first iPhone. In the UK, the housing market was booming. Admittedly, that euphoria was built on an unstable mountain of debt and the country was only two years away from the worst recession in living memory. But the mood was buoyant – as was economic growth.

UK economic growth is slow: should interest rates be 5%?

Nobody could argue that economic conditions today remotely resemble the prevailing optimism back then. Clearly, interest rates need to fall. But what, then, is the new ‘natural’ level for UK base rates? I’m prepared to be wrong, but a combination of structural factors leads me to believe that it is meaningfully lower than 3.5%.

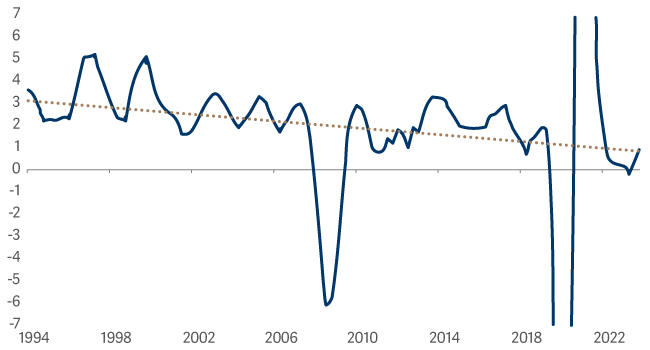

The basic fact is this: the trend rate of economic growth in the UK has slowed from 3% a year to 1% a year over the course of my career.2 The bad news is that I can’t see this improving, for three main reasons.

The trend rate of GDP growth has slowed from 3% to 1% since 1994

1. Debt levels are higher today. The UK’s debt-to-GDP ratio has increased from about 35% to 100% over the course of my career.3 That has boosted consumption and growth – but that process might now be nearing its limit. Sadly, the consumption and quality of life the country has been enjoying on credit means it will have less to spend tomorrow. As a country, we have enjoyed ourselves; now we must suffer the hangover.

2. The one-off boost from China joining the WTO is over. China’s entry to the WTO in 2001 led to massive and rapid industrialisation, brought millions of new workers (and consumers) into the global economy and gave a powerful boot to global economic growth. That is now largely behind us.

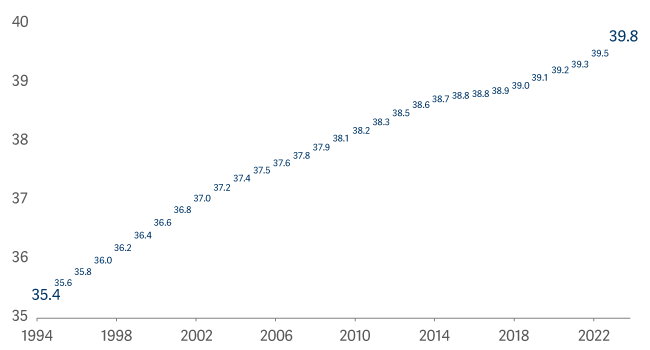

3. Demographics are not in our favour. When my younger colleagues tell me that I’m getting older, my rejoinder is that the world is aging more quickly than I am. And demographics are destiny. Consider Japan... When I began my career, my boss was taking weekly Japanese lessons. This was the era of blockbusters like Die Hard and Rising Sun, movies that expressed America’s worries that Japan was about to become the world’s dominant economic force. It didn’t. And the demographics have been one of the reasons why the Japanese economy has stagnated – and why it experienced negative interest rates for eight years.

The median age of the UK population has crept higher since 1994

It is possible that I’m wrong. Some deus ex machina, such as AI, might transform the UK’s economic prospects. But if I’m right and economic growth remains elusive, then rates seem likely to fall – and to fall much further than is currently predicted.

The silver lining for bond investors

A long period of economic stagnation would, of course, be bad news for a government hoping to grow its way out of a debt trap and bad news for our indebted society – but it could be good news for bonds. One other thing the past 30 years have taught me is that, for bond investors, almost every cloud has a silver lining.

2Source: Bloomberg as at 30 June 2024

3Source: House of Commons Public Finances: Key Economic Indicators 20 September 2024