How to react to turmoil in the gilt market

Liam O'Donnell explains what is behind the recent spike in UK borrowing costs and what this means for bond investors.

Sometimes you can over complicate what’s driving daily market moves, trying to link price action to politics, economic data releases and structural changes in saving or spending.

For bond investors, these factors are important in framing a structural view but carry little weight over very short time horizons. Sometimes our daily office debate ends with someone just muttering glibly: “More sellers than buyers.” Simple, yes. But, actually, as good an explanation as I have found for the recent turmoil.

Sometimes our daily office debate ends with someone just muttering glibly: “More sellers than buyers.”

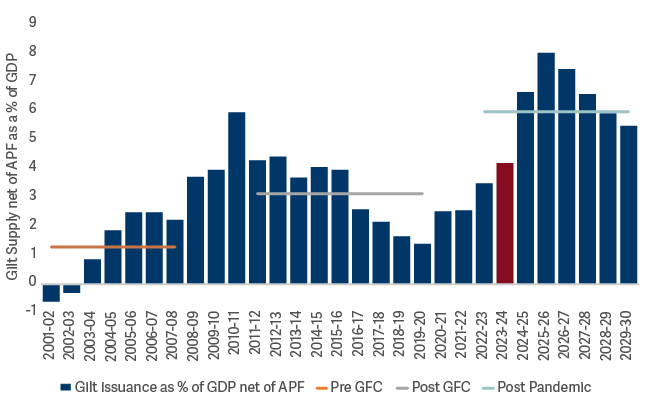

First, the sellers. Think back to last October’s Budget and what it meant for gilt issuance. It is worth repeating the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) comments.

“Over the five-year forecast period, gross gilt issuance averages 8.6% of GDP and net issuance averages 3.9% of GDP, an average of 0.9 and 0.7 percentage points higher than our March forecast respectively. This is largely due to the policy package announced at this Budget which adds 0.9% of GDP to net gilt issuance on average compared to our pre-measures forecast.

“The historically high cash requirement, alongside the unwinding of APF [Asset Purchase Facility] gilt holdings by the Bank of England, means the private sector needs to absorb historically high volumes of debt for a sustained period.

“The forecast for the change in private sector holdings peaks this year at 9.0% of GDP and averages 6.5% of GDP over the forecast period, compared to 2.7% of GDP between 2000-01 and 2022-23.”

Net Gilt Supply

Price-sensitive buyers

So the UK is issuing record levels of government bonds. And here’s the problem – it’s doing so into a market of increasingly price-sensitive buyers. This is a structural change versus the post-Global Financial Crisis/Covid era where price-insensitive central banks and pension funds were large buyers of government bonds.

We had two gilt-supply events in the first full working week of January, but with so much concern about the direction of yields, those buyers were hesitant. Starting the new year with a big hole in your profit & loss after just one month is not a good look. In the meantime, CTA (commodity trading advisor) and systematic accounts, which have been playing the UK from the short side, were big sellers. They will remain so until momentum turns.

So what’s making buyers so nervy? It goes back to the October Budget. While it wasn’t nearly as shocking as the Liz Truss Budget of 2022, growth is undershooting OBR forecasts.

Consequently, more UK government debt is required to maintain spending. Inflation is too high for the Bank of England to cut rates to stimulate the economy, meaning higher yields and therefore higher servicing costs for the UK government to service the nation’s debt. There’s a negative feedback loop here, and that’s the concerning part.

UK gilts are in the crosshairs for bond vigilantism. The worst outcome is just a continued selling pressure with few willing to step in to provide support. You can see why buyers are reticent about stepping in at this point. We’re only just seeing the deluge of Q1 bond supply hitting the market (EU/UK sovereign and investment grade).

UK gilts are in the crosshairs for bond vigilantism.

And then there is the backdrop. More broadly, Q4 2024 brought a significant shift to global politics/fiscal policy dynamics that has potentially large consequences.

In the UK, the chancellor’s decision to re-write fiscal rules to allow her to inject significant fiscal stimulus into the economy looks like having a long-lasting impact on sentiment towards UK gilts in a market already scarred by Truss. It did not help that many of the measures were unfunded and immediate.

Not just the UK

The theme of greater ‘fiscal slippage’ and government largesse is not just a story in the US or the UK – Europe is also struggling to rein in government spending. A new government in Germany will undoubtedly want to spend more. The French government collapsed under Michel Barnier because the legislative branch refused to sanction spending cuts to bring the budget deficit below 5% in 20251.

Political control is far more fragile across the eurozone, meaning fiscal discipline is unlikely. The pressure falls on government bonds, leading to higher yields as funding requirements and servicing requirements grow steadily higher.

Inflation doesn’t help. While economic performance varied considerably between the US, UK and Europe and across other developed markets, a consistent theme in 2024 was that core inflation remained too high. Services inflation in particular proved stickier than forecast.

That’s perhaps because of increased demand due to government spending and the fact that many of us have been enjoying healthy real wage gains for the first time in years2. It leaves central banks little room to manoeuvre on policy rates.

Why we’re focusing on shorter-maturity bonds

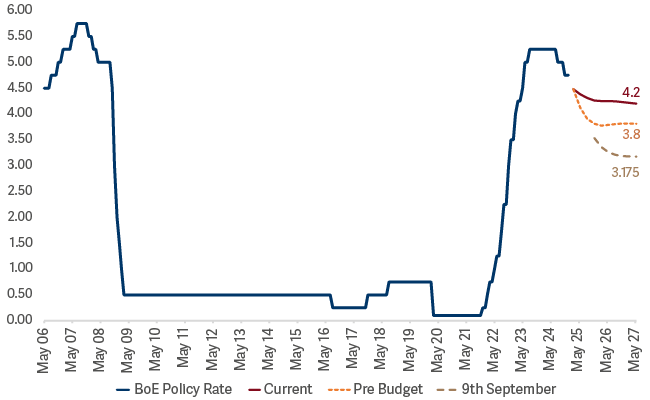

While we are aware of the risks to bonds from the supply/sentiment channel, valuations matter too. A key determinant is the current level of policy rates and their expected path. This is even more crucial for shorter-maturity bonds, an area of fixed income that looks extremely attractive to us.

At the start of October, markets priced neutral rates in the US below 3%. Currently this lies around 4.25% (versus the Federal Open Market Committee projection of 3%)3. In the UK, markets currently project the Monetary Policy Committee rate to drop only marginally over the next few years, settling around 4.2%. With policy rates currently at 4.75%, this implies just 50bps of cuts over the next few years4.

Market Pricing - Bank of England Base Rate

This repricing in rate expectations has created another opportunity for investors to look at shorter-maturity fixed income assets. Shorter-maturity bonds are in the unique position of yielding largely the same as longer-dated bonds. For UK government bonds, buying 10-year versus two-year only gives an additional 0.3%5. Additionally, these bonds are less vulnerable to the threat of rising supply and more closely tied to policy rate expectations.

We have been adding exposure to front-end rates strategies versus longer-dated rates. Ultimately, we expect this episode to blow over, but why challenge it when shorter-dated bonds offer similar levels of yields to their longer counterparts with a fraction of the risk?

Those yields look very compelling. For an investor seeking real returns, short-dated bonds seem to us to be an attractive buy today – despite the gloomy headlines.

2https://tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/wage-growth#:~:text=Wages%20in%20the%20United%20Kingdom,percent%20in%20March%20of%202009

3https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-12-13/the-fed-s-neutral-interest-rate-what-is-it-and-why-does-it-matter

4https://www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/news/258916/how-much-will-the-bank-of-england-cut-interest-rates-in-2025.aspx

5Bank of England